Nitrogen addition promotes SOIL MICROBIAL CARBON FIXATION IN AGRICULTURAL SOIL: A laboratory-based study

Nitrogen addition promotes SOIL MICROBIAL CARBON FIXATION IN AGRICULTURAL SOIL: A laboratory-based study

Abstract

The global carbon cycle is aided by soil autotrophic bacteria, which are crucial for storing atmospheric CO2. There are few reports of carbon-fixing bacteria in agro-soils, despite the fact that their potential to improve soil fertility has not been thoroughly investigated. The response of carbon-fixing bacterial populations to nitrogen addition in agricultural croplands is unknown. In order to investigate the effects of organic (cellulose) and ammonium salt solution treatments on soil organic carbon (SOC) and autotrophic soil bacterium abundance, a 54-day laboratory microcosm experiment was created. The quantity of crucial carbon cycle genes, such as cbbL and cbbM, is influenced by ammonium and organic inputs, which in turn alters the microbial community. The main soil factors affecting the quantity of carbon-fixing bacteria were the SOC and microbial biomass carbon. These results suggest that adding cellulose, the primary ingredient in wheat straw, and fertilizing with nitrogen may raise SOC, enhancing the soil fertility and carbon content of agricultural soil. According to the findings, more investigation is required to ascertain how ammonium and plant residues impact the diversity and activity of the soil's autotrophic microbial communities as well as how to manage them. The information can be used to determine safe and efficient dosages of ammonium fertilizers and plant wastes for modern, environmentally friendly agriculture in central Russia.

1. Introduction

Land use has a major influence on soil carbon (C) storage, which is much higher in the soil than in the plant and atmospheric C pools . Due to intricate interactions between microbial populations, soil qualities, and climate impacts, croplands — which cover approximately 12% of the planet's surface area — are a dynamic interface where organic materials originating from plants are continuously changing . By 2050, croplands are predicted to expand by 21% globally, potentially resulting in a 4.6% decrease in soil carbon storage . There is disagreement over the underlying mechanisms causing these changes, though.

In addition to moderating SOC turnover, soil microorganisms also contribute to the regulation of ecosystem processes by using SOC as an energy source for growth and reproduction . Microorganisms in agricultural soils are sensitive bioindicators of soil carbon cycling under various fertilization techniques and land use types, according to . Changes in the soil environment brought about by changes in land use may have an effect on the biomass, activity, and functional genes of soil microbes involved in carbon cycling. On the other hand, little is known about how microorganisms react to modifications in management techniques . By analyzing how land-use changes affect soil microbial biomass and gene abundance, we may better understand how microorganisms mediate carbon sequestration and create a theoretical framework for protecting soil carbon sinks.

Numerous researches in agricultural soils have examined the effects of plant residues on the diversity and activity of soil microorganisms. It has been demonstrated that adding agricultural residues to the soil improves community structure, increases the variety of soil microorganisms, increases the soil's organic matter and nutrient content, and strengthens its buffering capacity , , . The amount that microbial biomass contributes to the global C stocks in natural and agricultural ecosystems worldwide is largely unclear, despite the fact that it is a major source of soil carbon .

Microorganisms in the soil have the ability to absorb CO2 and transform it into SOC. An important marker of this process is the enzyme ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO), which is responsible for the Calvin cycle's initial rate-limiting phase . Because most previous research has focused on soil microbial C degradation rather than C fixation, the regulatory mechanisms for soil C fixation remain unclear . The most significant C-fixation process for microbes is the Calvin cycle. The two main and most researched varieties of RubisCO enzymes are form I and form II. The major subunits of RubisCO form I and II are encoded by the cbbL and cbbM genes, respectively. The autotrophic carbon-fixing bacterial populations in the environment may be molecularly analyzed using these two functional genes as particular probes since they are highly conserved and have the right gene length .

Studies employing the cbbM gene are less common than those utilizing the cbbL gene, which encoded Form I RubisCO, which was discovered in a variety of soil types and habitats . SOC was found to be positively connected with the abundance of carbon-fixing phyla Acidobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Cyanobacteria, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria . In addition to SOC, other environmental factors can have a significant influence on the community of carbon-fixing microbes, and nitrogen fertilization treatments can significantly alter the community's diversity and makeup .

According to our hypothesis, the addition of nitrogen to agricultural soil will enhance its ability to fix carbon and encourage the growth of microbial biomass, including autotrophic bacteria, as well as the microbial breakdown of wheat straw. Our hypothesis was tested by measuring the dynamics of soil microbial activity (CO2 production), microbial biomass (SIR technique), abundance of carbon-fixing bacteria (qPCR analysis of cbbL and cbbM genes), and SOC content (dichromate oxidation) simultaneously in a 54-day microcosm experiment using agricultural soil. The conditions in the soil following the harvest of wheat and the plow-in of straw as organic fertilizer were replicated in a soil microcosm experiment. The study aimed to provide insights for evaluate microbial mechanisms.

2. Research methods and principles

For our microcosm study, we employed gray forest loamy-clay soil (Gleyic Phaeozems) that was being used for wheat cultivation. About 100 kilometers south of Moscow, Russia, on the right bank of the Oka River, near the village of Pushchino (54.8oN, 37.6oE), was the sample site. Samples of mixed soil were collected from the surface horizon in September 2024. Soil was sampled and processed for analysis as described in . Prior to the start of the studies, the soil was maintained at 4oC.

In February 2025, the microcosm experiment got underway. Ten grams of soil with 25% moisture content were put into 100 ml vials. In thermostats, microcosms were incubated for 54 days at 25°C while the soil moisture content remained constant. Cellulose (0.5 percent of the soil weight) was applied to the soil to simulate the addition of straw in situ. 100 µg N/g of ammonium sulfate solution was used to simulate N-fertilization. As described in , the substrate induced respiration method (SIR) was used to evaluate the microbial respiration and biomass in the soil.

Following the manufacturer's recommendations, 0.25 g of soil samples were used to extract soil DNA using the DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Using SYBR Green I technology in a PCR buffer-RB (Syntol, Russia) with the passive reference dye ROX present, real-time PCR was used to count the copies of the 16S rRNA, cbbL, and cbbM genes in the soil samples. Using the LightCycler 96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Roche), the proper primer sets , and a temperature-time profile were applied.

The information is displayed as three-sample averages. The observed treatment effects were deemed statistically significant at p<0.05 in all investigations. Excel was used to do the statistical analysis (Microsoft Office Excel 2011).

3. Results and discussion

Because SOC affects the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of soil, it is crucial for enhancing soil fertility and maintaining soil productivity. The amount and quality of SOC can be altered by a number of management techniques, including as tillage, fertilization, and the return of straw. While the contribution of autotrophic bacteria is still unknown, it is generally known that crop leftovers are a source of organic matter and that they frequently enhance the amount of organic C in soil when they are returned.

In the current investigation, we ascertained the dynamics of autotrophic bacterial abundance in soil microcosms with cellulose addition (Control) and observed that the number of these bacteria marginally increased over the course of a 56-day incubation period in samples containing ammonium supplements (Ammonium) (Table 1). During the first week of incubation, the number of cbbL genes — which are thought to be important genes for identifying autotrophic bacteria — in Ammonium microcosms doubled, and it stayed that way for the duration of the following time. The quantity of cbbL genes in the Control soil remained essentially constant. The dynamics of the cbbM gene showed a similar pattern (Table 1).

The cbbM gene was substantially more abundant than the cbbL gene. The range of cbbL gene abundance in ammonium-amended samples was 1.10-2.47 × 106/g d.w.s., while in Control samples it was 1.30-1.66 × 106/g d.w.s. The cbbM gene's abundance varied between 81 and 139 × 106/g d.w.s. and did not substantially differ (p ˃0.05) between the control and ammonium application groups. After 14 days of incubation, an increase in the quantity of autotroph genes was seen (Table 1), demonstrating the autotrophs' ability to proliferate in that brief amount of time.

The percentage (%) of possible carbon-fixing bacteria in the bacterial community that use RubisCO I and RubisCO II via the Calvin cycle was calculated using the 16S rRNA and the abundances of the cbbL and cbbM genes. The percentage of the cbbM gene was substantially greater than that of the cbbL gene in all samples (p< 0.05). The cbbM/16S rRNA ratio varied from 0.94 to 1.5%, whereas the cbbL/16S rRNA ratio ranged from 0.011-0.019%. There was no significant difference in the ratio between the Control and Ammonium variants for both genes.

Studies of soil environments actively exploit the abundance of the cbbL genes . In soil ecosystems, autotrophic carbon-fixing bacteria participate in carbon sequestration. Their interactions with environmental elements like biomass, microbial activity, and soil organic carbon (SOC) may hold the key to understanding soil and restoration biology. The abundances of the Calvin cycle functional genes cbbL and cbbM were calculated in this work, and their dynamics showed a similar pattern. The abundance of the cbbL and cbbM genes (106–108 copies/g d.w.s) in the agricultural soils suggested that there is, in fact, a sizable population of autotrophic carbon-fixing bacteria present. These genes were generally more abundant in our study than was found in paddy soils, with 105–108 copies/g d.w.s .

In the current investigation, the cbbM gene was substantially more abundant than the cbbL gene. This discrepancy might be the result of surface soil sampling, where the growth of carbon-fixing bacteria with the cbbL gene may have been suppressed by the increased O2 concentration .

Table 1 - Abundance of total bacterial (16S rRNA) and RubisCO (cbbL and cbbM) genes during the soil incubation experiment

Experimental variant | Incubation, days | 16 s rRNA, × 109/g d.w.s. | cbbL, × 106/g d.w.s. | cbbM, × 106/g d.w.s. |

Control | 0 | 8.74 ±0.43 | 1.30 ±0.06 | 109.00 ±3.7 |

14 | 8.96 ±0.26 | 1.38 ±0.07 | 104.00 ± 6.21 | |

28 | 8.54 ±0.33 | 1.66 ± 0.05 | 87.80 ±4.33 | |

42 | 9.24± 0.64 | 1.28 ± 0.06 | 139.00 ±6.28 | |

56 | 8.65± 0.45 | 1.39 ±0.07 | 81.00 ± 4.21 | |

Ammonium | 0 | 7.96 ±0.62 | 1.10 ±0.06 | 94.50± 3.22 |

14 | 9.74 ±0.36 | 2.12 ±0.05 | 117.00 ±7.00 | |

28 | 9.36 ±0.72 | 2.28 ±0.07 | 117.00 ±6.87 | |

42 | 9.61 ±0.46 | 2.47 ±0.06 | 119.00 ±6.34 | |

56 | 9.91 ±0.51 | 2.13 ±0.07 | 123.20± 5.48 |

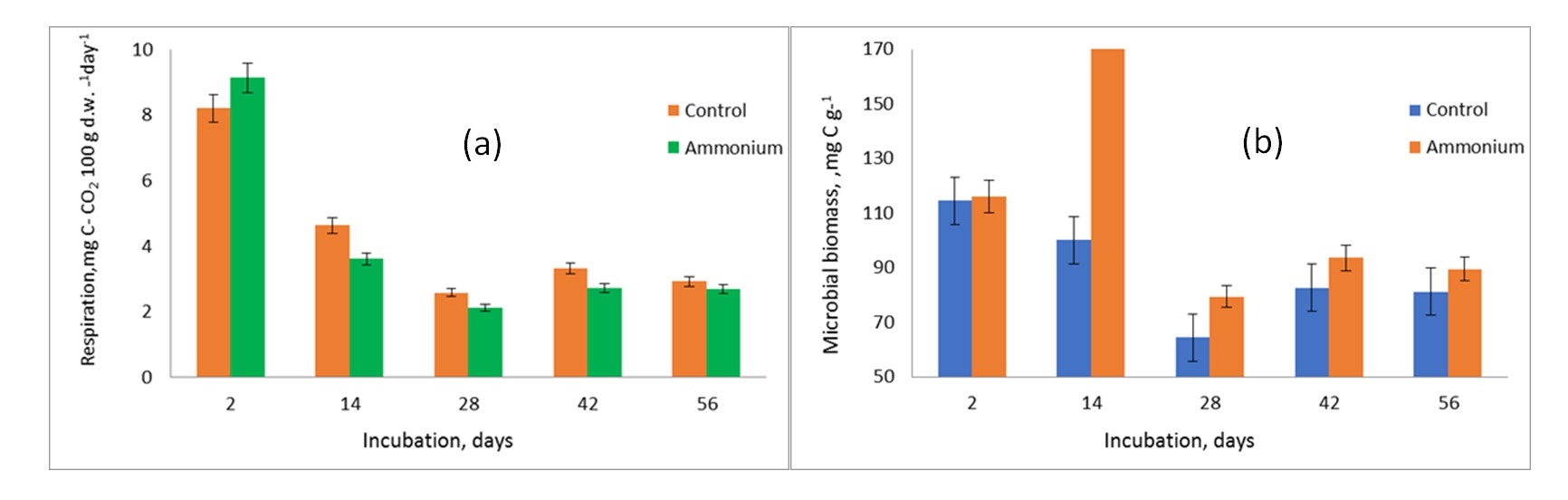

The biggest flux of CO2 from terrestrial ecosystems to the atmosphere is soil respiration, which is also a crucial indication of soil biological activity . Both variations' microbial respiration, as determined by CO2-C, showed a clear peak at the start of incubation (Fig. 1), but the N-amended variants' respiration rates were higher. N assimilation and increased availability of cellulose's readily decomposable organic matter components could account for the first increase in CO2-C seen on days 2–14. Because soluble straw substrates are more nutrient-available to microorganisms, they are preferred by soil microbes over native SOC, and extra N fertilizer speeds up the breakdown of plant litter .

Following two weeks of incubation, the Ammonium variant's respiration activity was considerably lower than that of the Control (o <0.05). Because nitrite is formed through nitrify action, N treatments lowered the pH values of the soil .

Figure 1 - Dynamics of on CO2 efflux rate (a) and microbial biomass (b) of soil microorganisms in soil samples amended with cellulose (Control) and cellulose plus nitrogen (Ammonium)

Dead microbial biomass makes up the microbial biomass C pool (MBC), which constitutes 1–3 percent of the total soil organic carbon (SOC). It controls the breakdown and production of organic C in soils and serves as a general measure of the level of soil microbial activity. In addition to being a major force behind soil N mineralization, microbial biomass is crucial for the breakdown of organic matter and the cycling of nutrients . Crucially, assessments of soil fertility , soil effective nutrient status, and biological activity frequently rely on the size of the microbial biomass and associated fluxes.

Additionally, microbial MBC contributes carbon to soil humus, and the new humus it fosters benefits soil ecology and fertility. Although these increases are temporary, prior research has shown that the size of the MBC pool tends to rise proportionately to the amount of exogenous N supplied; this relationship may be due to the lower soil C/N ratio that nitrogen application promotes . In line with patterns seen in larger SOC pools, some research also indicates that N deposition modifies the MBC pool more in grasslands than in forests or croplands . Moreover, MBC is a source of C contributing to soil humus, and the new humus formation that it promotes supports soil fertility and ecology .

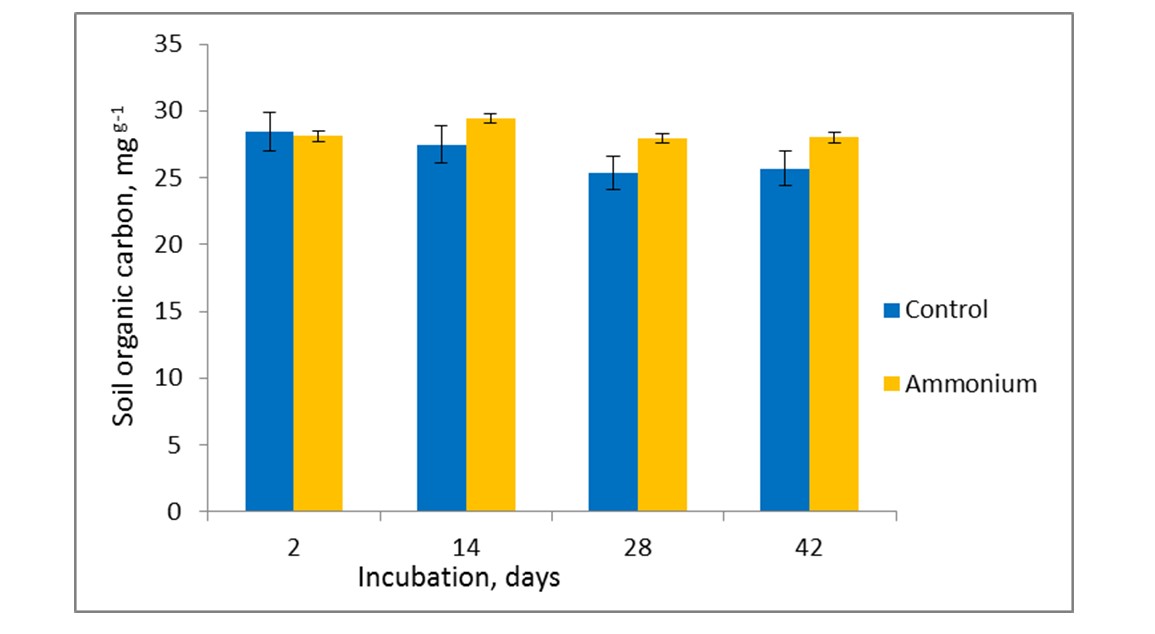

Figure 2 - Dynamics of active organic C content during incubation experiment

The correlation study revealed that there were substantial positive connections (r = 0.759) between the copies number of ccbM genes and Corg (r = 0.637) and between CO2-C and microbial biomass (r = 0.754). We came to the conclusion that the abundance of the carbon-fixing bacterial community was significantly impacted by both soil microbial biomass and Corg. It is well known that soil Corg has an impact on the biological and physicochemical traits of soil and is crucial to soil ecosystems . The organization of the carbon-fixing bacterial population may be impacted by changes in various soil carbon factors . In the subtropical region of China, it was found that the Corg content was the primary factor influencing the organization of the soil autotrophic carbon-fixing bacterial community in soils with varying tillage patterns . Their findings are similar to those of the current agricultural soil study.

The taxonomic structure of the facultative and obligate autotrophic bacterial communities in the soil is unknown at this time. Nonetheless, published research suggests that there is a heterogeneous community of autotrophic bacteria. According to phylogenetic research, facultative autotrophs Azospirillum, Rhodopseudomonas, Bradyrhizobium, and Ralstonia were the most prevalent cbbL-containing bacteria in China's subtropical upland soil. More environmental circumstances can be adapted to by facultative autotrophic microorganisms. They can use organic carbon sources for energy and carbon assimilation in addition to growing autotrophically through the Calvin cycle. Consequently, variations in Corg contents could result in variations in the structure of the soil's carbon-fixing bacterial population.

4. Conclusion

The research presented here demonstrates the considerable potential for microbial assimilation of atmospheric CO2 in agricultural soils. It was shown the influence of nitrogen application on soil C stability in the agricultural soil and revealed its novel driving underlying mechanism — a sizable number of autotrophic carbon-fixing bacterial communities that possessed two essential enzymes, RubisCO form I and form II. This investigation serves as a theoretical reference for soil carbon sequestration in agricultural soils, as well as implications for the successful enhancement of soil fertility.

The cbbM genes encoded RubisCO form II may play a more important role in CO2 fixation cbbL genes in the agricultural soil, while local edaphic factors (pH, clay content, C/N ratio, SOC) may significantly influence gene diversity. Further studies involving transcripts of these marker genes, alternate CO2 assimilation pathways, and field studies are all required. These will eventually contribute to a better understanding of the ecological role of the autotrophy in soil C cycle, and improving the soil carbon-fixing potential.